Blog post

What is Synthetic Fraud?

Charlie Custer

Published

April 29, 2024

Synthetic identity fraud is a large-scale problem. SentiLink catches more than 7,000 instances of synthetic fraud per day for our partners, and we see it everywhere, from banking to auto lending to healthcare.

Let’s take a closer look at what synthetic identity fraud is, what it’s costing financial institutions, and how it can be identified and treated.

What is synthetic fraud?

What is synthetic fraud?

Synthetic identity fraud involves creating a fake identity and using it to perpetrate fraud. We define a synthetic identity as a name, DOB, and SSN that don't all belong to the same cohesive real person. For example, a fraudster might make up a name, DOB, and SSN combination, and use that new identity to apply for a loan or open an account at a credit union.

Synthetic identity fraud is also sometimes called “Frankenstein fraud,” because in some cases it involves mixing together pieces of legitimate identity information with entirely fake information, evoking Dr. Frankenstein’s mixture of body parts to create a monster in Mary Shelley’s classic horror novel. However, synthetic identity fraud does not always fit this “Frankenstein” pattern.

The term synthetic fraud is used to describe a variety of different things.

The two main types of synthetic fraud

First-party synthetic fraud describes when a fraudster uses their true name and date of birth, but an SSN that doesn’t belong to them. This is also sometimes called identity manipulation.

First-party synthetic identity fraud is generally associated with people manipulating their own identities intentionally, using a fake SSN to disassociate themselves from the credit history associated with their true identity. However, it is also possible that first-party synthetic applicants have been tricked by disreputable credit repair agencies, who encourage them to use a credit privacy number (CPN) or similar nine-digit number instead of their true Social Security number.

Third-party synthetic fraud describes when a fraudster invents a synthetic identity wholesale, combining a name, DOB, and SSN that are not associated with a real person. This is also sometimes called identity fabrication.

Third-party synthetic identity fraud is often associated with organized crime.

While those two terms describe the two most common approaches to synthetic fraud, there are a variety of ancillary types and subtypes. For a detailed discussion and taxonomy of these, please refer to our white paper on defining synthetic fraud.

How synthetic identity fraud happens: an example

How synthetic identity fraud happens: an example

Synthetic identities are surprisingly easy to create. It’s as simple as taking your own name, date of birth, and any nine-digit number that looks like a Social Security number and applying for a loan.

Pre-2011 SSNs follow predictable patterns; the first 3 digits of your SSN indicate where the SSN was issued, and the next 2 digits provide additional information about when the SSN was issued. SentiLink calls these first five digits your SSN5. In 2011, the Social Security Administration switched to randomized SSNs, which have a different set of possible SSN5s.

Synthetic fraudsters can generate plausible fake SSNs by starting with a post-2011 random SSN5 and adding four random digits to the end of it. Most possible random SSN combinations have either not been issued yet or have been issued to children under 18, who will not yet have credit records, so there is little likelihood of picking an SSN that is in use by anyone else.

Synthetic fraudsters can also make use of SSN5s from earlier than 2011, particularly SSN5s issued in recent years, such that the recipient is still likely to be a minor (as of this writing, 2006-2011).

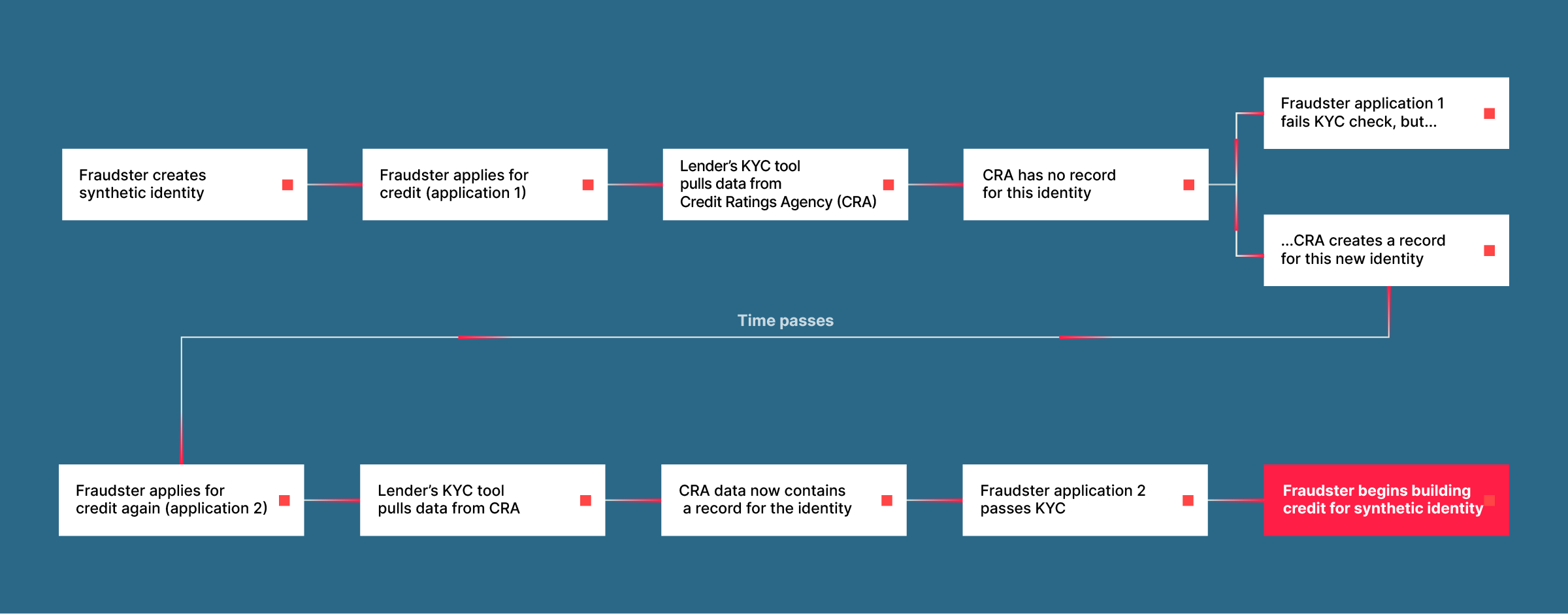

When a fraudster applies with the synthetic identity and fake SSN they’ve just created, they will get declined for that initial loan. However, the act of applying for credit creates a record at the credit bureau with the name, date of birth and made-up Social Security number used to apply. This newly-created record is a synthetic identity.

With this newly-minted synthetic identity, there are a variety of ways to build credit. The traditional way is to prove creditworthiness over a long period of time. For example, a fraudster might apply for a $500 secured line of credit, and pay it off. Next, they might apply for and subsequently pay off a $500 line of unsecured credit. Then a $1,000 line of unsecured credit, and so on. It can take years to increase the credit score on this synthetic identity to the 700-750 range, at which point it can get approved for much higher amounts of credit.

Or, there are a variety of shortcuts. One is authorized user tradelines. These have been available on credit cards for a long time. It’s common for parents to list their teenage kids as authorized users on their credit cards so their kids can have access to higher credit lines and lower pricing, and for spouses to share cards and rewards points. With the rise of authorized user tradeline marketplaces, however, there’s no need to rely on a family member or friend to become an authorized user. Countless online marketplaces now allow fraudsters to pay strangers to become an authorized user on their credit card.

Disreputable credit repair agencies are another tactic fraudsters use to increase the credit score on their synthetic identities. There are a host of companies that are magnets for fraudsters looking to quickly season their synthetic identities. These companies typically look like online retailers, but are actually a type of credit repair agency offering unsecured lines of credit that anyone can purchase to boost their credit score.

Once the synthetic identity has a high credit score, fraudsters “bust out," applying for large loans at legitimate lenders that they will never repay.

Summary: the three phases of synthetic identity fraud

In short, typical synthetic identity fraud occurs in three phases:

First, the fraudster creates a fake identity, using either a mix of real and fake information or wholly fake information. They apply for credit and are denied, but this application creates a credit file for their synthetic identity at the credit bureaus.

Second, the fraudster builds credit, either by applying for and paying back smaller loans and credit lines, or through other tactics such as purchasing authorized user tradelines or other credit boosting products.

Third, after the synthetic identity’s credit score is high enough, the fraudster uses it to “bust out,” maxing out all of their available credit with no intent to repay.

Red flags and patterns to watch for

Red flags and patterns to watch for

Identifying a synthetic identity is tricky because synthetic identities circumvent the Know Your Customer solutions most financial institutions use to remain compliant with banking laws.

KYC guidelines require FIs to form a “reasonable belief” that they know the true identity of the consumer. But most KYC solutions work by checking the data on the application against credit header data they purchased from the credit bureaus to see if the incoming application data matches an existing record. As demonstrated above, establishing a new record at the credit bureaus is an incredibly simple process.

Thus, KYC solutions generally will validate synthetic identities – they see that a credit record exists for the synthetic identity, and that is generally all the proof they require to pass the KYC check.

Synthetic fraudsters are also frequently able to bypass many traditional fraud treatment strategies, so institutions should not count on being able to catch them via step-up measures such as government ID, phone, or address verification. First-party synthetic identities may have (for example) real drivers licenses, aged phones and emails, and utility bills.

Correctly identifying a synthetic identity requires data and insight to determine if the SSN provided belongs to a given name and DOB combination. In broad strokes, some patterns to look at include:

- Whether the provided SSN makes sense in relation to the other information on the application, such as date of birth and address.

- Whether the applicant identity appears to match better with a different SSN, or has little to no history with the provided SSN.

- Whether the applicant or application information have links to addresses associated with known cases of fraud.

- The SSN window

- Whether the applicant’s name/DOB/SSN combo passes eCBSV verification.

- Whether there are other “proof of life” signs in available data indicating that the applicant is a real person.

How to detect and prevent synthetic fraud

How to detect and prevent synthetic fraud

Identifying synthetic fraud accurately often requires access to data from a wide variety of historical sources. Addresses in the applicant’s history, phone and email history, patterns in DOB/SSN combos, and more – all may be relevant in identifying synthetic fraud. Connections between credit applications to different institutions over time can also play a role. Having this data is critical because, as previously mentioned, synthetic fraudsters can often defeat traditional fraud treatment strategies such as step-up ID verification.

Fortunately, organizations can make use of purpose-built solutions that leverage a broad variety of financial and public data to identify likely cases of synthetic identity fraud. SentiLink, for example, provides a score that indicates the likelihood that an incoming application is using a synthetic identity.

SentiLink was also the first provider to integrate with the Social Security Administration’s eCBSV service, so SentiLink’s partners can leverage eCBSV verification seamlessly to provide a strong signal as to whether the name, DOB, and SSN in a given application match what the SSA has on record. Verifying the name, DOB, and SSN against a source-of-truth database such as the SSA’s is the single best treatment strategy for synthetic identity fraud.

Typically, we recommend eCBSV as a step-up treatment strategy, rather than a top-of-funnel check. This is in part because it requires collecting written consumer consent, and in part because our experience with eCBSV indicates the majority of mismatches (two-thirds, in fact) are not due to fraud, but are instead the result of input typos and other non-malicious inconsistencies (such as legal name changes). If applied at the top of the funnel, these mismatches could lead to false-positive denials.

Instead, eCBSV should be viewed as a step-up check when fraud is suspected to quickly confirm whether a name/DOB/SSN combination is legitimate, or whether further investigation is required.

Learn more about the intricacies of synthetic fraud in our white paper: Defining Synthetic Fraud.

Related Content

Blog article

March 12, 2026

How Human Intelligence Drives Model Performance in Fraud Prevention

Read article

Blog article

March 10, 2026

What Happened to Identity Fraud Rates in 2H 2025?

Read article.png)

Blog article

February 20, 2026