Blog post

The Complicated Landscape of Assumed Identity Fraud

John Chang, Chief of Staff, R&D

Published

December 20, 2023

Assumed identity fraud occurs when a consumer applies for a financial product using the PII of another individual who was previously in the United States on a visa but is no longer in the United States. Oftentimes, these individuals were in the U.S. for seasonal work or as part of an exchange program for work or studying. Sometimes, this is identity theft. As data breaches have reached record levels, few people are immune to having their data being stolen and used for nefarious reasons. But other times, the individual whose identity is being used (the “assumed identity”) is complicit in the activity, either by intentionally sharing or selling access to their SSN.

Detecting visa fraud

This behavior is challenging to detect for two reasons:

- Because SSNs were legitimately issued to the assumed identities, they will pass verifications by the SSA through eCBSV or an SSA-89 form.

- Because the assumed identity is not in the United States, it’s unlikely that the financial institution will successfully contact the individual to confirm whether the activity is legitimate or fraudulent, which is a condition for classifying a case as identity theft.

Instances of assumed identity fraud can look similar to third-party synthetic fraud. Specifically, SSNs can appear to belong to a child or thin-file consumer because there is little or no history tied to them with the credit bureaus. Additionally, these identities may exhibit quickly growing credit history within a relatively short time. Lastly, often the SSN is issued in a state that doesn’t align with the address on a financial application. The natural treatment strategy for third-party synthetic fraud is eCBSV, but as noted above, visa fraud would avoid such detection.

Typical patterns

We looked at 3 classes of signals to identify applications which are instances of suspected assumed identity fraud:

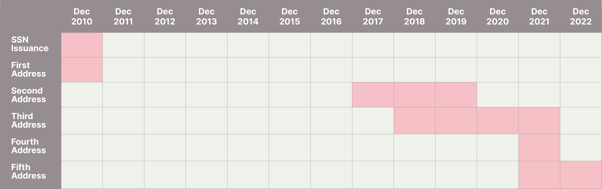

- History gaps: A common way of identifying this type of behavior is looking at the history of the consumer. Specifically, there is often a gap in credit history between the SSN issuance date and when more substantial credit activity appears.

In one instance, we saw a consumer with a short address history in Alaska in 2010. The next instance this consumer appeared in the financial services ecosystem was in 2017 in California – the 7 year gap in the consumer history is a clue pointing to this being an instance of assumed identity fraud.

- Ties to bad addresses: Many of the same addresses appear on the credit reports of the assumed identities. This is likely because those addresses actually belong to one of the individuals involved in perpetrating the fraud, allowing them to comfortably access credit cards and other financial documents sent by mail intended for the victim.

- SSN issuance state to address history state mismatch: Legitimate consumers who apply for an SSN would have financial activity in the same state as where the SSN was issued. However, sometimes there is activity in other states but little to no activity in the SSN issuance state. This pattern, especially when seen with a gap in credit history, is cause to suspect assumed identity fraud.

Little recourse

For most financial institutions, in order to tag losses as fraud, the consumer victim needs to be identified. Since most of the victims, whether complicit or not, are no longer in the United States, this is unlikely to happen. As a result, the losses are often misattributed to credit losses as opposed to fraud losses.

Once a financial institution identifies a suspected instance of assumed identity fraud, there are multiple treatment strategies available, including:

- Tax transcript verification: Although the SSA would recognize the supplied name, DOB, and SSN combination, it’s unlikely that up-to-date tax transcripts would be available for these consumers. As a result, verifying whether recent tax transcripts are available, such as through a 4506-C, would likely be an effective treatment. Discovering that no tax transcripts exist for the same time period as when credit activity occurs would support the case being an instance of assumed identity fraud.

- Drivers license or government ID verification: Since many of these individuals were only in the U.S. for a limited period of time, it’s unlikely that many received real government issued IDs. For those who did, those IDs may be expired or inaccessible to the fraudster. However, simply checking IDs may be insufficient because sophisticated fake IDs are easily obtainable now. Instead, going forward and checking against a database such as AAMVA may be effective.

Conclusion

Assumed identity fraud continues to be a nuanced fraud behavior that requires specific strategies to catch. If you haven't already signed up to receive updates on our ongoing research into assumed identity fraud, please let us know here.

Related Content

.png)

Blog article

February 20, 2026

Romance Fraudsters Have Found a New Target: Your Home Equity

Read article

Blog article

February 19, 2026

Introducing SentiLink Intercept: Precision Tools for High Stakes Fraud Decisions

Read article

Blog article

December 2, 2025