Blog post

Old Student IDs, New Scams: How a Burbank Ring Recycles Visiting-Scholar Identities

David Maimon

Published

November 7, 2025

When foreign movie stars and professors start showing up in the same fraud files, something unusual is happening. The pattern was unmistakable: a surge of credit applications, all tied to foreigners who'd left the US years ago. Celebrities. Professors, Graduate students. All sharing the same California addresses, the same IP addresses -- identities resurrected from dormancy by someone who knew exactly where to find them. What began as a series of identity-theft cases involving international celebrities quickly evolved into something far more deliberate — a coordinated operation rooted in Southern California, exploiting the dormant identities of those who once came to America to study, teach, or perform.

In recent weeks, my colleagues and I have traced the operation to Burbank, California -- a quiet pocket of Los Angeles better known for movie studios than organized crime. Beneath its tree-lined streets and low-rise apartment complexes, this fraud network specializes in resurrecting the identities of former international students and visiting scholars — individuals who studied in the U.S. during the early 2000s and 2010s, and whose personal information remains scattered across school databases, credit bureaus, and outdated records. Using local apartment addresses and shared IPs to make their activity appear legitimate, the ring has been systematically applying for new accounts at multiple banks and credit card companies in these individuals’ names.

First Clues

A few weeks ago, we spoke with one of our partners about the growing use of foreign celebrities’ identities in fraud attempts. Because a foreign movie star working in the United States needs a Social Security Number (SSN) or an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN) to get paid legally and meet their U.S. tax obligations, celebrity identities are often targeted by fraudsters and tend to be quickly flagged by fraud detection systems. What caught our attention in this recent wave of identity theft attempts involving foreign celebrities, however, was the pattern: a high volume of applications submitted simultaneously to major credit issuers, all originating from the same California-based addresses — and, in some cases, even from the same IP addresses. Out of curiosity, we decided to dig deeper into other applications linked to those same addresses and IPs. We quickly discovered that the fraudsters were also using the identities of another group of foreigners frequently seeking to live and work in the U.S.: foreign students and scholars.

Every year, hundreds of thousands of international students arrive in the United States to pursue higher education. They come with ambitious goals—expected to carry full course loads, maintain strong GPAs, and often juggle on-campus jobs to keep their visa status active. At the same time, they must quickly adapt to an unfamiliar education system that emphasizes independence, participation, and financial responsibility.On top of these academic and cultural adjustments, foreign students are required to navigate a uniquely American set of administrative obligations: opening a bank account, applying for a Social Security number, and registering an address with their school. For most, these steps mark the beginning of their academic journey in America. But when these individuals leave the country, their American identities remain behind—dormant but still active in financial systems. These identities can become valuable targets for fraudsters. The same fraud ring exploiting foreign celebrity identities has also used the identities of many former international students and professors in attempts to open new bank accounts and credit lines.

The Investigation

To investigate this trend, we analyzed a sample of applications flagged by our systems as Assumed Identity Abuse that were submitted to our partners at the end of September 2025. We discovered that a significant number of these applications were submitted within a short time frame, across several partners, and shared striking similarities — including overlapping California-based IP addresses and recurring California-based mailing locations. Most of the new account applications originated from residents of apartment buildings linked to just six major addresses.

Apartments in these buildings were listed as part of the identity theft applications

The sample revealed a diverse group of foreign students and scholars who had studied or worked in the United States between 1977 and 2024 before leaving the country. Their LinkedIn profiles confirmed that many of these individuals had legitimate ties to U.S. institutions but were no longer residing in the country.

Example 1

Example 1

Example 2

Example 2

The records suggest that these individuals resided in more than a dozen U.S. states, including academic and research hubs in Pennsylvania, New York, California, Massachusetts, and Texas. Other locations represented include Arizona, Connecticut, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Indiana, Tennessee, New Jersey, Illinois, and Florida.

The foreign scholars in this dataset come from a range of countries, though Turkey stands out as the most represented, accounting for nearly half of all entries. Other notable countries include Japan and India, followed by single entries from the Netherlands, Portugal, Greece, Australia, and England.

Durations of stay vary significantly. Some individuals remained in the U.S. for just a year or two, while others stayed more than a decade. Several records show no departure dates, indicating either incomplete data or individuals who may still reside in the U.S. The earliest arrival dates trace back to the late 1970s, while the most recent departures occurred as recently as 2024.

Who is behind this?

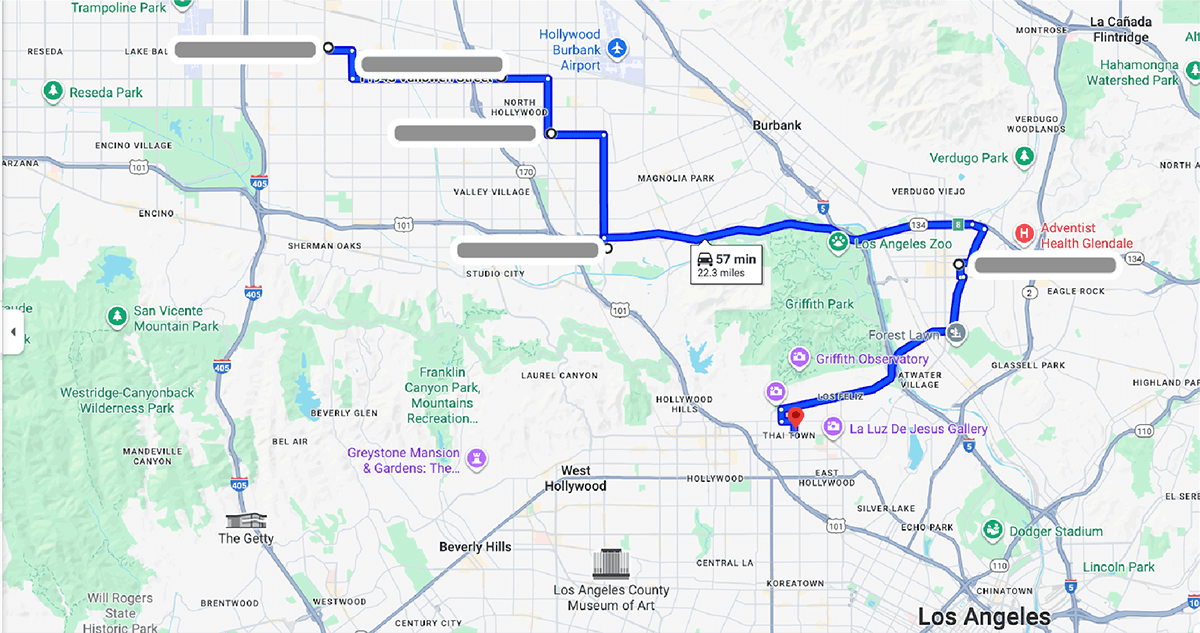

Because many of the applications originated from the same handful of California-based addresses, we decided to estimate the distances between them to understand their geographic proximity. Focusing on the six addresses associated with the highest number of applications using former foreign student identities, we plotted them on Google Maps and calculated the most efficient driving route. The analysis revealed that the two most distant addresses were approximately 22 miles apart—a distance that can be covered by car in under an hour. The approximate centroid of those six addresses falls around the Griffith Park-Burbank border area — specifically near Victory Blvd & Riverside Dr, around Burbank, CA 91505. This area is known to be part of the territory of the Armenian Power (AP also known as AP-13) organized crime group (their territory includes Glendale, Burbank, Hollywood, and Little Armenia).

Armenian Power is a long-standing, predominantly Armenian-American organized crime group rooted in Southern California. Formed in the late 1980s in East Hollywood and Glendale, the group began as a youth street gang created to protect Armenian teens from larger Latino gangs. Over time, AP evolved into a hybrid network that blurred the line between street gang and organized crime syndicate, forging alliances with other criminal organizations including the Mexican Mafia. Today, their influence extends across Glendale, Burbank, Hollywood, and the San Fernando Valley, where members maintain a foothold through both traditional gang activity and more sophisticated financial schemes.

What sets Armenian Power apart from many other Los Angeles–based gangs is its focus on white-collar and financial crime. Law enforcement investigations — most notably the 2011 Operation Power Outage led by the FBI, ICE, and LAPD — revealed a sprawling enterprise involved in bank fraud, credit card cloning, synthetic identity creation, staged insurance scams, and unemployment and tax refund fraud. AP members frequently operated under the cover of legitimate businesses, including auto repair shops and insurance offices, to facilitate their schemes and launder profits. While drug and weapons trafficking have played a secondary role, the group’s ties to Russian-speaking and Eastern European criminal networks helped them expand their reach into international money-laundering operations. Despite federal indictments that disrupted the organization’s leadership, smaller AP factions continue to operate across Los Angeles County, focusing on digital-era financial fraud and identity theft.

While we cannot be entirely certain that this specific group is responsible for the surge in applications using the identities of former foreign students and professors, several indicators point strongly in that direction. First, the addresses associated with the stolen identities fall squarely within Armenian Power’s traditional territory in Southern California. Second, a significant portion of the compromised identities belong to individuals of Turkish origin, a pattern that aligns with known ethnic and regional dynamics surrounding the group’s membership and rivalries. Third, Armenian Power has a long and well-documented history of engaging in large-scale identity theft, credit fraud, and financial scams, often relying on sophisticated methods and insider access to carry out their operations.

Taken together, these factors suggest more than coincidence. The overlap between geography, victim demographics, and the group’s criminal expertise points to a likely connection between Armenian Power’s ongoing financial-fraud activity and the recent wave of identity theft involving former foreign academics. While conclusive attribution requires additional evidence, the convergence of these data points offers a compelling lead for further investigation.

Conclusions

The pattern emerging from this investigation reflects a concerning evolution in the tactics of organized financial fraud. What began as a series of scattered identity theft attempts involving foreign celebrities has revealed a broader and more systematic exploitation of dormant identities — specifically, those of former international students and scholars who once studied or worked legally in the United States. The evidence points to a well-coordinated network operating from within Southern California, likely leveraging local addresses, shared infrastructure, and regional familiarity to scale its operations. While direct attribution remains pending, the geographic, demographic, and behavioral consistencies observed suggest that the fraud activity is neither random nor opportunistic. Rather, it appears to be the work of an experienced group with a history of sophisticated financial schemes, consistent with known patterns of organized crime in the region.

Beyond the immediate financial risks, this case underscores a deeper vulnerability in the U.S. identity and credit ecosystem: the persistence of digital and financial records tied to individuals who have long since left the country. These dormant identities, often still valid in institutional databases, are increasingly being weaponized by organized groups that specialize in data-driven financial crime.

Addressing this emerging threat requires a coordinated response that bridges financial institutions, federal regulators, and academic organizations. First, credit issuers and banks should consider implementing specialized screening protocols for applications that include foreign identities with long inactivity periods or recently reactivated SSNs or ITINs. Enhanced linkage between academic exit data and credit bureaus could help flag dormant records before they are repurposed for fraud.

Second, universities and research institutions should adopt more secure offboarding processes for departing international students and scholars. This may include securely archiving sensitive identifiers (such as SSNs issued for campus employment) and partnering with federal agencies to mark such records as inactive once visa programs conclude.

Finally, a broader policy conversation is needed around how identity systems manage the long tail of legitimate but dormant credentials. As organized crime networks increasingly blend traditional street-level operations with white-collar cyberfraud, protecting these identities is not only a matter of financial security — it’s a matter of safeguarding trust in the institutions that welcome, employ, and educate global talent.

Related Content

Blog article

December 2, 2025

The Identity-Theft Risk Profile of NBA and NFL Draft Prospects

Read article

Blog article

November 21, 2025

CIP Requirements: What Financial Institutions Need to Know

Read article

Blog article

November 7, 2025